Hai-mu Yao, Tong-wen Sun, You-dong Wan, Xiao-juan Zhang, Xin Fu, De-liang Shen, Jin-ying Zhang, Ling Li

1Department of Cardiovascular Disease, First Af fi liated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 400052, China

2Department of Integrated ICU, First Af fi liated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450052, China

Corresponding Author:Tong-wen Sun, E mail: suntongwen@163.com

Domestic versus imported drug-eluting stents for the treatment of patients with acute coronary syndrome

Hai-mu Yao1, Tong-wen Sun2, You-dong Wan2, Xiao-juan Zhang2, Xin Fu1, De-liang Shen1, Jin-ying Zhang1, Ling Li1

1Department of Cardiovascular Disease, First Af fi liated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 400052, China

2Department of Integrated ICU, First Af fi liated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450052, China

Corresponding Author:Tong-wen Sun, E mail: suntongwen@163.com

BACKGROUND:The application of coronary stents, especially drug-eluting stents (DESs), has made percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) one of important therapeutic methods for CHD. DES has reduced the in-stent restenosis to 5%–9% and signi fi cantly improved the long-term prognosis of patients with CHD. The study aimed to investigate the long-term ef fi cacy and safety of domestic drugeluting stents (DESs) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

METHODS:All patients with ACS who had undergone successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the First Af fi liated Hospital of Zhengzhou University from July 2009 to December 2010 were included in this study. Patients were excluded from the study if they were implanted with bare metal stents or different stents (domestic and imported DESs) simultaneously. The included patients were divided into two groups according to different stents implanted: domestic DESs and imported DESs.

RESULTS:In the 1 683 patients of this study, 1 558 (92.6%) patients were followed up successfully for an average of (29.1±5.9) months. 130 (8.3%) patients had major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs), including cardiac death in 32 (2.1%) patients, recurrent myocardial infarction in 16 (1%), and revascularization in 94 (6%). The rates of cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction, revascularization, in-stent restenosis, stent thrombosis and other MACEs were not signi fi cantly different between the two groups (all P>0.05). Multivarite logistic regression revealed that diabetes mellitus (OR=1.75, 95%CI: 1.09–2.82, P=0.021), vascular numbers of PCI (OR=2.16, 95%CI: 1.22–3.83, P=0.09) and PCI with left main lesion (OR=9.47, 95%CI: 2.96–30.26, P=0.01) were independent prognostic factors of MACEs. The Kaplan-Meier method revealed that there was no significant difference in cumulative survival rates and survival rates free from clinical events between the two groups (all P>0.05).

CONCLUSIONS:The incidences of clinical events and cumulative survival rates are not statistically different between domestic DESs and imported DESs. Domestic DES is effective and safe in the treatment of patients with ACS.

Acute coronary syndrome; Percutaneous coronary intervention; Drug-eluting stent; Cardiovascular adverse events

INTRODUCTION

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is a disease of cardiac ischemia, anoxia, and necrosis, caused by coronary artery atherosclerosis. In recent years, the incidence of CHD has increased markedly.[1]The application of coronary stents, especially drug-eluting stents (DESs), has made percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) one of important therapeutic methods for CHD. DES has reduced the in-stent restenosis to 5%–9% and significantly improved the long-term prognosis ofpatients with CHD.[2]The wide use of DES has made it possible for the treatment of complex coronary lesions with PCI, and the clinical effect of imported DES has been proved by numerous clinical trials.[3–5]After domestic DES, Firebird, was put into use, other DESs have been developed. With the improvement of manufacturing technology of domestic stents and interventional techniques, domestic DESs have been widely used in clinical practice. But the long-term efficacy and safety in a large scale clinical trial of domestic DESs was sparsely determined. The aim of the present study is to estimate the long-term efficacy and safety of domestic DESs in patients with ACS.

METHODS

Ethics statement

The present study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. The data were anonymous and therefore no additional informed consent was required.

Study population

This study was carried out in consecutive patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who had undergone PCI from July 2009 to December 2010 at the Cardiovascular Department, First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, China. Only patients who were treated with at least one DES and had a long-term follow-up were recruited in the current study. Patients were excluded from the study if they were implanted with bare metal stents or different stents (domestic and imported DESs) simultaneously. The patients were divided into a domestic DES group and an imported DES group according to different stents implanted. Qualitative and quantitative coronary angiographic analyses were performed according to the standard methods. PCI was performed using standard techniques. All patients were given loading doses of aspirin (300 mg) and clopidogrel (300 mg) before the coronary intervention, unless they had already received these antiplatelet medications more than 5 days. Treatment strategy, stenting techniques, selection of stent type, as well as use of glycoprotein IIb/ IIIa receptor inhibitors or intravascular ultrasound were all left to the operator's discretion. Aspirin (100 mg) and clopidogrel (75 mg) were prescribed daily for at least the fi rst 12 months after the procedure.

Clinical outcomes and data collection

Data of the patients were put into a database containing demographic, clinical, angiographic, and procedural information. Primary end points included all-cause death, occurrence of myocardial infarction (MI), in-stent restenosis, stent thrombosis, and revascularization. The composite end points were de fi ned as major adverse cardiac events (MACEs), namely death/non-fatal MI/revascularization. Stent thrombosis was proven by angiography, or assumed as probable if an unexplained sudden death occurred within 30 days after stent implantation, or if a Q-wave MI was diagnosed in the distribution area of the stented artery. This classi fi cation was issued according to de fi nitions proposed by the Academic Research Consortium (ARC): acute (<24 hours), subacute (24 hours to 30 days), late (1–12 months), and very late (>12 months).[6]All deaths were considered to be cardiac unless an unequivocal noncardiac cause could be established. Cardiac deaths included all events related to a cardiac diagnosis, any complication of a procedure and treatment thereof, or any unexplained cause. Unexpected death, even in patients with a coexisting and potentially fatal noncardiac disease (e.g., cancer or infection), was classified as cardiac unless their history relating to the noncardiac diagnosis suggested death was imminent. Clinical follow-up was carried out through patient visits, telephone interview, and medical record review. The data of the patients were put into the database by independent research personnel, and clinical events were defined by an independent committee. Between July 2009 and December 2010, 1 683 patients met the criteria. At last, the data of 1 558 patients (92.6%) were collected in a follow-up period of 29.1±5.9 months (range 25.3–33.4 months).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Nomally distributed continuous variables were analyzed using Student's t test. The variables whose distribution could not be assumed to be normal were analyzed using Wilcoxon's rank-sum test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Cumulative survival was constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare curves. Logistic regression analysis was made to identify the independent predictors of MACE. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and P value<0.05 was considered statistically signi fi cant. All data were analyzed using SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

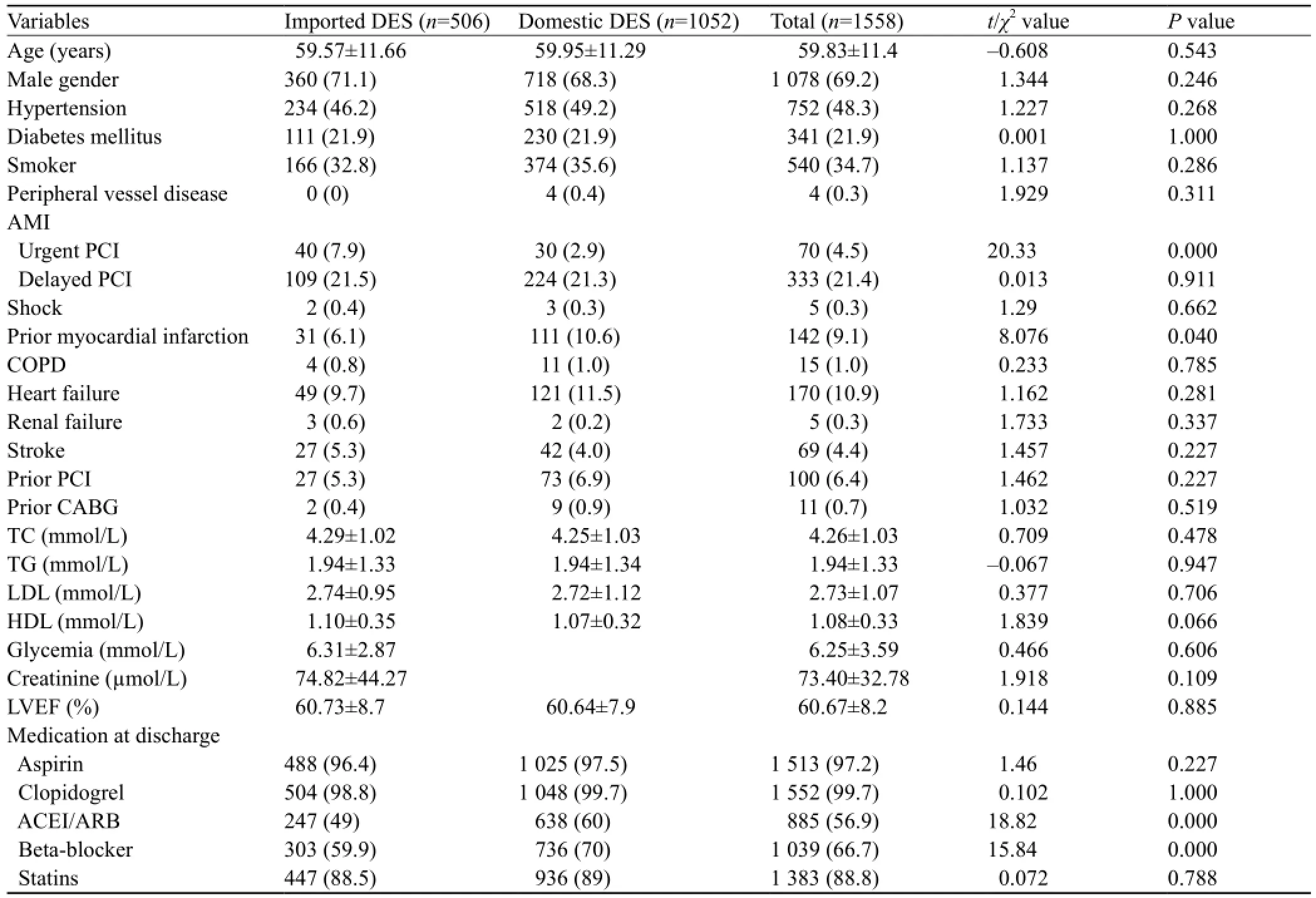

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics (n, %)

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study groups

Demographic characteristics of the 1 558 patients are shown in Table 1. Of the patients, 1 078 (69.2%) were men and the mean age of the patients was 59.8±11.4 years. There were 752 (48.3%) patients with hypertension, 341 (21.9%) with diabetes mellitus, 540 (34.7%) patients with a history of smoking, and 403 (25.9%) patients with acute MI.

The proportion of patients who underwent urgent PCI was signi fi cantly higher in the imported DES group than in the domestic DES group, but the proportion of patients with a history of old myocardial infarction was significantly lower. The percentage of patients treated with β-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/ angiotensin receptor inhibitor, and low weight molecular heparin was significantly higher in the domestic DES group than in the imported DES group. There was no significant difference in age, gender, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and the history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure, renal failure, and stroke between the two groups.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics

Angiographic and procedural characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 2. Over 98% cases of PCI were performed through the radial artery. There were 382 (24.5%) patients with multi-vessel lesions and 50 (3.2%) patients with left main stem (LM) lesions. Compared with the domestic DES group, the frequency of single vessel lesion was significantly higher (47.4% vs. 35.5%, P<0.01), and the frequencies of LM lesion, two-vessel or multi-vessel lesion, right coronary artery lesion, and long lesion were significantly lower in the imported DES group. In contrast, patients treated with domestic DESs involved more vessels and received more and longer stents than those treated with imported DESs.The percentages of ostial lesion, bifurcation lesion, total occlusion lesion, and the diameter of stent were not signi fi cantly different between the two groups.

Table 2. Baseline angiographic and procedural characteristic (n, %)

Table 3. Baseline angiographic and procedural characteristics (n, %)

Clinical outcomes

The incidence of MACE was approximately 8.3%, including 2.1% for cardiac death, 1% for recurrent myocardial infarction, and 6% for revascularization. The frequencies of all deaths, such as recurrent myocardial infarction, revascularization, in-stent restinosis, stent thrombosis, and MACE were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis

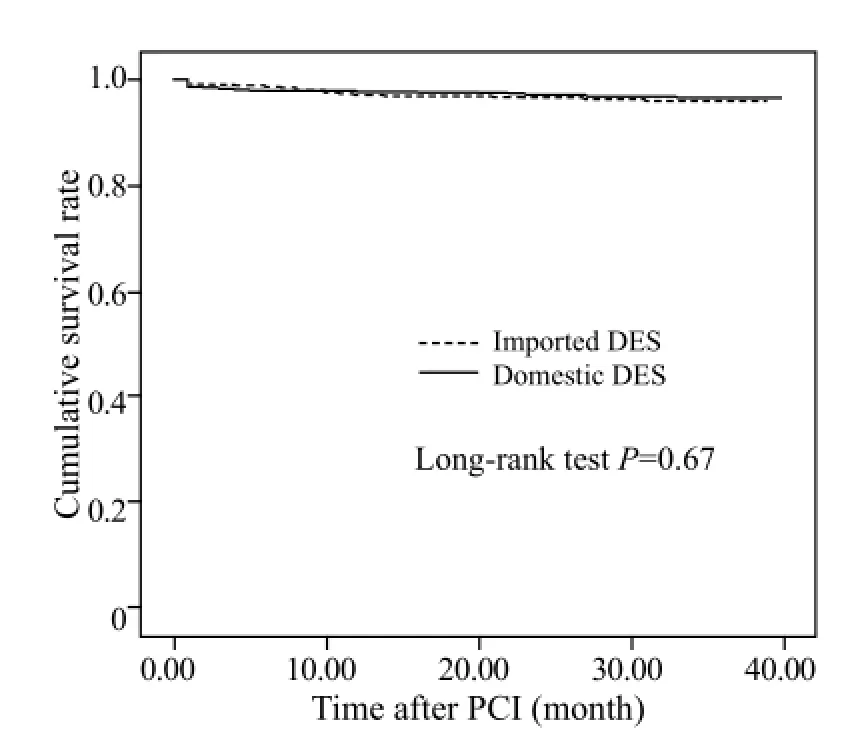

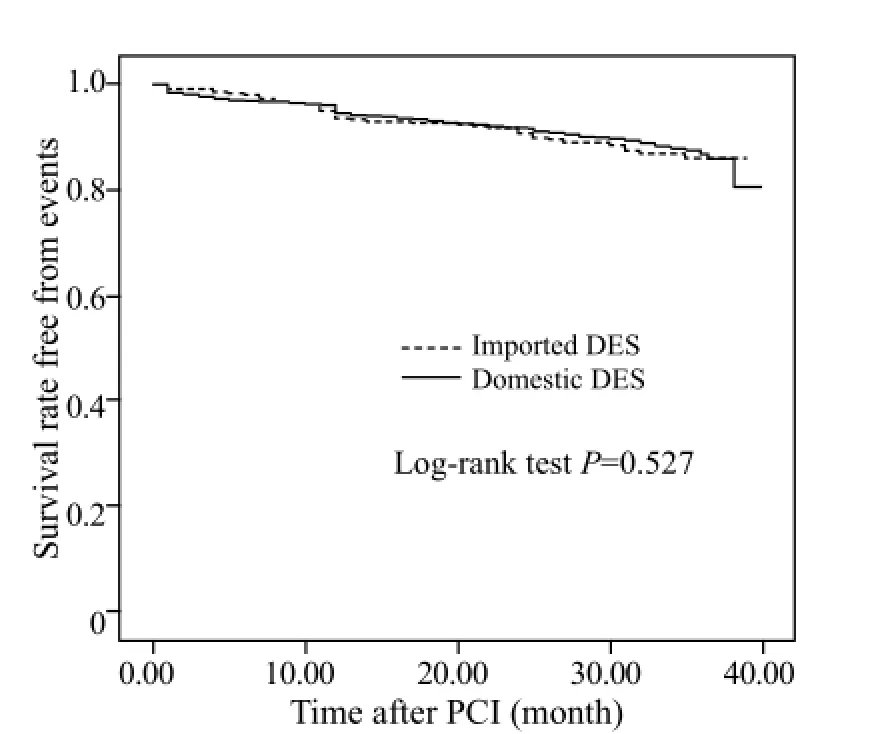

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the independent risk factors for MACE. The following variables were examined: age, gender, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, peripheral vessel disease, cerebrovascular disease, left ventricular ejection fraction, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass graft, heart failure, renal insufficiency, location of lesion, number of diseased vessels, location of target lesion, number of treated vessels, urgent PCI, number of stent, total stent length, stent diameter, and the type of stent. The results showed that the independent risk factors for MACE were diabetes mellitus (OR=1.75, 95%CI: 1.09–2.82, P=0.021), number of treated vessels (OR=2.16, 95%CI: 1.22–3.83, P=0.09), and target vessel =LM (OR=9.47, 95%CI: 2.96–30.26, P=0.01) (Table 4). The Kaplan–Meier method revealed that the cumulativesurvival rate (P=0.67, Figure 1) and the cumulative survival rate free from clinical events were not signi fi cantly different between the two groups (P=0.527, Figure 2).

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression of risk factors for major adverse cardiac events

Figure 1. The cumulative survival rates of the two groups.

Figure 2. The cumulative survival rates free from clinical events of the two groups.

DISCUSSION

PCI has opened a new era of CHD treatment. Although bare metal stent implantation has significantly reduced the incidence of early cardiac adverse events of PCI, in-stent restenosis has been a problem. The main mechanism of in-stent restenosis is the hyperplasia of intima and vascular smooth muscle. Rapamycin, paclitaxel and their derivatives are currently main drugs contained on DES. Both the two types of drugs could inhibit the hyperplasia of intima and vascular smooth muscle. The clinical trials have proved that DES can not only prevent the in-stent restenosis caused by early postoperative vascular wall recoil and long-term negative remodeling, but also can significantly reduce the in-stent restenosis caused by smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia. Though some studies[7,8]have found that DES could increase the risk of late stent thrombosis, clinical trails have proved that DES could significantly improve the long-term prognosis of patients with CHD.[3,4,8–10]

Since domestic DES Firebird was marketed in 2003, several other types of domestic DES have been put into clinical practice. With the improvement of manufacturing technology of domestic DESs, they have been used clinically in recent years. Domestic DESs have accounted for over 60% of total stents used in our hospital. Some studies[11–14]compared the clinical ef fi cacy of domestic DESs with imported DESs, but they had a small sample size, limited to single stent comparison and speci fi c patients. The present study enrolled the patients with ACS who underwent successfully PCI from July 2009 to December 2010 in our hospital, including use of domestic DESs available at that time.

In our study, there were no statistical differences in causes of death, cardiac death, recurrent MI, revascularization, in-stent restenosis, stent thrombosis, and MACE between the two groups. These results were consistent with those of previous studies.[13–16]

The proportion of patients treated with urgent PCI was significantly higher in the imported the DES group than in the domestic DES group (7.9% vs. 2.9%) in our study. Some studies showed higher incidences of adverse events in patients treated with urgent PCI. Because of the lower proportion of patients treated with urgent PCI (4.5%), the impact on the overall results was limited in our study. The frequency of single vessel lesion was significantly higher and the number of stent implanted was signi fi cantly lower in the imported DES group than in the domestic DES group. Whereas the frequencyof long lesions, the number of treated vessels, and the total stent length were significantly higher in the domestic DES group than in the imported DES group. This result is consistent with the actual condition in our hospital. In this study, most of the patients came from rural areas, and when more stents were needed domestic DES was the first choice in consideration of the cost. Previous studies[17,18]indicated that the degree of vascular lesions, multi-vessel diseases, and stent length were predictive factors of in-stent restenosis. The present study also found that the number of treated vessels was an independent predictor of MACE, which further con fi rmed the ef fi cacy and safety of domestic DES.

Because of the lack of small diameter domestic DESs, only imported DESs with a 2.25 mm diameter were used. The incidence of in-stent restenosis was higher in patients treated with small diameter stents.[17]When patients treated with small diameter stents were removed from the population in our study, the incidence of clinical events was not signi fi cantly different between the two groups. Since XIENCE V stent was marketed after the enrollment of our study, the production of cypher stent was stopped, the significance of this study on future clinical practice needs to be further evaluated.

In the present study, the incidence of clinical events was lower than that previously reported.[3]There are several explanations for this finding. First, the low frequency of follow-up angiography may underestimate the incidence of in-stent restenosis. Second, China is a developing country where health insurance and costs are likely to deter most patients from undergoing subsequent revascularization procedures. Third, our study included all eligible patients, and some of them were lost to follow-up, which may have a higher incidence of clinical events.

In our study, the proportion of patients who were prescribed β-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker was signi fi cantly higher in the domestic DES group than in the imported DES group. But its precise reason is not clear. Both of the drugs may have an impact on the long-term prognosis of patients with CHD, but the impact of these drugs on the results of the present study is unclear.

Limitations

Our study also has some limitations that should be considered. First, the present study is a retrospective observational study based on registration data, there are some differences in baseline clinical characteristics which may affect the results. Second, the study is a single-center registry study. Third, the small proportion of patients undergoing follow-up angiography, may underestimate the frequency of in-stent restenosis. Last, the rates of successful PCI with different stents were not reported. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, this study was a large-scale study estimating the long-term ef fi cacy and safety of patients with ACS who were implanted domestic DES. Large-scale randomized controlled studies are needed to further estimate the efficacy and safety of domestic DES.

In conclusion, the incidences of clinical events and cumulative rates of survival were not statistical different between the domestic DES and imported DES groups in this study. Domestic DES is effective and safe in patients with ACS. Given the large price difference between imported DES and domestic DES as well as the huge population of patients with CHD in our country, the promotion of domestic DES can greatly reduce medical costs and make more patients bene fi t from it.

Funding:This study was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81370364), Innovative Hnvestigators Project Grant from the Health Bureau of Henan Province, Program Grant for Science & Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province (2012HASTIT001), Henan Provincial Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Project (122102310581), Henan Province of Medical Scienti fi c Province & Ministry Research Project (201301005), Henan Province of Medical Scientific Research Project (201203027), China.

Ethical approval:This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China.

Conflicts of interest:We have no conflicts of interest to this report.

Contributors:Yao HM proposed the study and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

REFERENCES

1 Ge J, Qian J, Wang X, Wang Q, Yan W, Yan Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the sirolimus-eluting stents coated with bioabsorbable polymer coating in human coronary arteries. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 69: 198–202.

2 Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O'Shaughnessy C, et al. Sirolimus -eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 1315–1323.

3 Park KW, Kang SH, Park KH, Choi DH, Lee HY, Kang HJ, et al. Sirolimus- vs paclitaxel-eluting stents for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis: Complete 2-year follow-up of a two-center registry. Int J Cardiol 2011; 151: 89–95.

4 Zahn R, Neumann FJ, Büttner HJ, Richardt G, Schneider S,Levenson B, et al. Long-term follow-up after coronary stenting with the sirolimus eluting stent in clinical practice: results from the prospective multi-center German Cypher Stent Registry. Clin Res Cardiol 2012; 10: 709–716.

5 Ogita M, Miyauchi K, Dohi T, Wada H, Tuboi S, Miyazaki T, et al. Gender-based outcomes among patients with diabetes mellitus after percutaneous coronary intervention in drug-eluting stent era. Int Heart J 2011; 52: 348–352.

6 Cutlip D, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical End Points in Coronary Stent Trials : A Case for Standardized De fi nitions. Circulation 2007; 115: 2344–2351.

7 Jensen LO, Maeng M, Kaltoft A, Thayssen P, Hansen HH, Bottcher M, et al. Stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and death after drug-eluting and bare-metal stent coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 463–470.

8 Wöhrle J. Stent thrombosis in the era of drug-eluting stents. Herz 2007; 32: 411–418.

9 Kim U, Kim DK, Kim YB. Long-term clinical outcomes after angiographically defined very late stent thrombosis of drugeluting stent. Clin Cardial 2009; 32: 526–529.

10 Chang K, Koh YS, Jeong SH, Lee JM, Her SH, Park HJ, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting for unprotected left main coronary bifurcation disease in the drug-eluting stent era. Heart 2012; 98: 799–805.

11 Mieres J, Rodríguez AE. Stent selection in patients with myocardial infarction: drug eluting, biodegradable polymers or bare metal stents? Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov 2012; 7: 105–120.

12 Zhou H, He XY, Zhuang SW, Wang J, Lai Y, Qi WG, et al. Clinical and procedural predictors of no-re fl ow in patients with acute myocardial infarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. World J Emerg Med 2014; 5: 96–102.

13 Xia K, Ding RJ, Hu DY, Yang XC, Wang LF. The efficacy and safety of transradial versus transfemoral approach for percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2011; 50: 478–481.

14 Kang WC, Ahn T, Lee K, Han SH, Shin EK, Jeong MH, et al. Comparison of zotarolimus-eluting stents versus sirolimuseluting stents versus paclitaxel-eluting stents for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: results from the Korean Multicentre Endeavor (KOMER) acute myocardial infarction (AMI) trial. EuroIntervention 2011; 7: 936–943.

15 Xu B, Dou KF, Yang YJ, Chen JL, Qiao SB, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of long-term clinical outcome after successful implantation of FIREBIRD and CYPHER sirolimus-eluting stents in daily clinical practice: analysis of a large single-center registry. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011; 124: 990–996.

16 Zhang F, Ge JB, Qian JY. Comparison of clinical outcomes between domestic sirolimus-eluting stent and bare metal stent in the primary percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin J Emerg Med 2007; 16: 1175–1179.

17 Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G, Trapani M, Bolognese L, Dovellini EV, et al. Primary stenting in non selected patients with acute myocardial infarction: the Multilink Duet in Acute Myocardial Infarction (MIAMI) trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2000; 51: 273–279.

18 Lee CW, Suh J, Lee SW, Park DW, Lee SH, Kim YH, et al. Factors predictive of cardiac events and restenosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in small coronary arteries. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007; 69: 821–825.

19 Kuntz RE, Safian RD, Carrozza JP, Fishman RF, Mansour M, Baim DS. The importance of acute luminal diameter in determining restenosis after coronary atherectomy or stenting. Circulation 1992; 6: 1827–1835.

Received February 20, 2014

Accepted after revision July 3, 2014

World J Emerg Med 2014;5(3):175–181

10.5847/ wjem.j.issn.1920–8642.2014.03.003